I’m Pregnant

If you're facing an unintended pregnancy or have recently given birth, we're here for you with free and confidential all-options counseling, resources, and support. Call or text our pregnancy counselors 24/7 at 800-439-0233.

If you're facing an unintended pregnancy or have recently given birth, we're here for you with free and confidential all-options counseling, resources, and support. Call or text our pregnancy counselors 24/7 at 800-439-0233.

Browse our network of adoption services including infant and foster care adoption, home studies, and post-adoption support.

Explore our network of services including specialized counseling and support groups that help to stabilize and improve behavioral health symptoms.

Looking for Adoptions Together or FamilyWorks Together? New name, same us. Here’s why!

Lorem ipsum featured quote

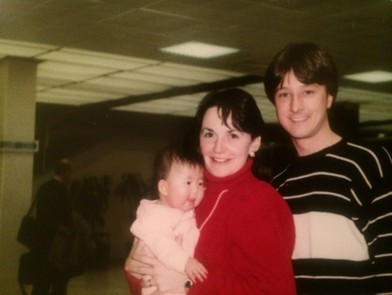

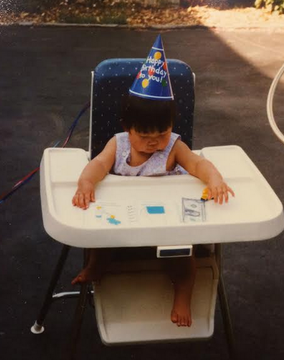

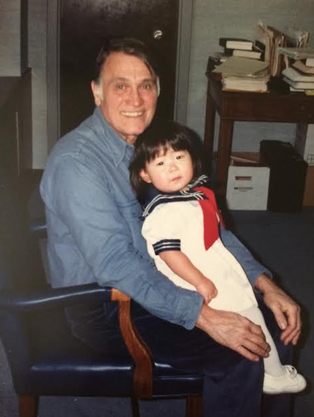

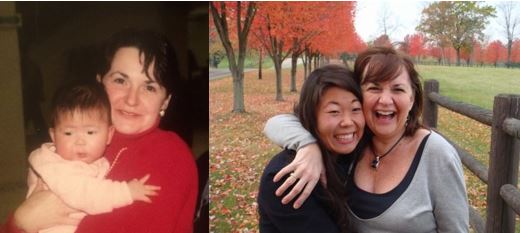

MY STORY

Recently, though, I realized that I never allowed myself to grieve for what I lost as an adoptee. At 25, I recognized that I never fully explored the feelings of rejection and confusion that often accompany adoption. Only now have I started to feel sad that I may never have the answers to certain questions: What does my birth mother look like? Did she hold me in the hospital before handing me over? Is she passionate, fiery, and emotional like me? Or is she quiet, reserved, and tranquil? Does she think about me often or did she repress all memories of her pregnancy and adoption plan?

I developed the ability to keep thoughts like these in check. I felt that because of the limited information my adoptive parents were given about my birth history, I had no choice but to fight off these feelings. Like most overseas adoption stories in the 1980s, it was shrouded in secrecy and stigma. It would have been too painful to wonder about the first 6 months of my life, knowing I might never have an answer. At an early age, I learned to respond to difficult questions with a smile. Kids on the playground would ask me: Where is your “real” mom? Why did she abandon you? Don’t you want to find her? Are you sad that she didn’t want you? My adoptive parents thankfully provided me with the tools to handle situations like these. I would explain to my inquisitive peers that not all families look alike and that my birth mother’s decision came from a place of love. Even adults asked questions, triggering my Rolodex of canned responses. Don’t you wish you had a picture of your birth mother? Yes, absolutely, I would say. If I were you, I would want to know every detail about my birth history. Oh, I agree wholeheartedly. Afterwards, I would either brush it off or feel guilty that I didn’t respond the “correct” way.

MY SEARCH

In the summer of 2012, I reached out to Spence-Chapin Adoption Services, the agency in New York that facilitated my placement in 1987. Within a few days, I was having conversations on the phone with the Korea Program Coordinator, Ben, about beginning my search. The process was simple and straightforward, he explained. It involved submitting a couple of basic forms. Even so, I dragged my feet when filling out the paperwork. At first, I chalked it up to being busy but I knew deep down it was my fear of the unknown. What if my birth mother doesn’t want to know me? What if, when I meet her, she doesn’t like me? What if I don’t like her? I remember thinking this search could turn my life upside down and I wasn’t sure whether I was emotionally prepared for that. I could reunite with my birth mother and find out she is happily married with children – and that might hurt me. Or, I could meet her and secretly dislike her and then feel guilty about it afterwards. What if I found out she was assaulted by my birth father? Would that impact my self-perception? Would I feel obligated to keep in touch with her forever? It was the first time I had ever let myself ask these kinds of questions.

A few weeks later, I received a call from Spence-Chapin. It was Ben. He greeted me in his normal, soothing voice. I sensed an uncomfortable pause, though, after we exchanged hellos. Before he could tell me the news, I realized she was no longer alive. He informed me that she had passed away in 2006. The wheels began to turn in my head while we spoke over the phone. She must have passed away while I was a freshman in college. She was only 65 years old. Had I known something was wrong, perhaps, I would have tried to reach out to her sooner. “Was she sick?” “Was it an accident?” His response crushed me. “I’m sorry but I can’t give you any more details.” It was because of the stringent adoption laws in Korea. She was my birth mother, though. I felt entitled to this information and wondered if it was all sitting in a file on his desk. For a minute, I even wondered if I could bribe him for answers. Was it cancer? Or was it unexpected? Were her other children there to comfort her? Shouldn’t I have access to my medical history? In that moment, I felt like my search came to a screeching halt.

I mourned a loss that was different from other losses I had experienced. I lost the chance to know my birth history. I lost the opportunity to meet my birth mother and show her the person I had become. I would never know her name or be able to hear the sound of her voice. In the months leading up to my search, I started to picture myself riding in a van with my adoptive parents to my birth mother’s home in Pusan. We would be ushered through a door by one of my birth siblings and greeted by an older Korean woman with a round, cherubic face. She would have tears running down her wrinkled face and say something profound like: “Not a day has gone by when I haven’t thought of you.” And despite any language or cultural barriers, we would understand each other. For the first time, I would recognize my face in someone else’s. My almond-shaped eyes and chubby cheeks would mirror hers.

It was hard to fathom this dreamlike sequence I had envisioned would never play out in real life. At the same time, I felt a huge sense of relief. While I consider myself to be a fairly strong person, I cannot say for sure that I would have been emotionally ready to handle any curveballs. What if I reached out to my birth mother and learned that she was not ready to have a relationship with me? Would it ruin her marriage or her relationships with her children, if I suddenly resurfaced in her life?

MY JOURNEY

A few months after submitting my application, I found myself on a plane full of Koreans heading towards Seoul. I remember naively thinking to myself: Where did all of these people come from? It was the first time I was part of what people call “the visual majority” as an adult. I chuckled at the ridiculousness of it all. I am surrounded by Korean people on a runway strip in Baltimore. While we waited for our plane to depart, I furtively watched a team of stylish flight attendants stow people’s luggage away with more elegance and grace than a ballerina. These women are flawless, I thought to myself. My clumsy American gait and wavy hair is going to make me stick out like a sore thumb once I get there.

In a way, my predictions were right. While store clerks and cab drivers appeared puzzled by my inability to speak Korean, numerous people would ask me if I was Japanese or Chinese. Even after straightening my wavy hair and buying dark-rimmed glasses to match the voguish women of Seoul, I often felt out of place. For the first time in my life, I was straddling two worlds. On one hand, I was surrounded by people who physically resembled me. To the eye of an unseasoned tourist, I blended in. To insiders, though, I felt self-conscious about my tan skin and wavy hair. I constantly worried that any minute someone was going to pick me out of the crowd and “out” me to everyone. They would point their SPF-moisturized finger in my face and scream in Korean: “IMPOSTER!” And, sure enough, I would stand there, mortified and confused, as the crowds dispersed around me. My paranoia dissipated as time went on. The people I met on my trip were welcoming, which made it easier for me to embrace myself in Korea.

During my time in Korea, I was able to let go of the insecurities that were weighing me down. I forgave myself for missing out on the chance to meet my birth mother. It was a hard pill to swallow, but I eventually realized that I was not ready to open that door growing up. And that is okay. I revisited my history on my own terms and at my own pace.

I also made a concerted effort towards the end of my trip to care less about my appearance. Growing up with Asian features in a predominantly white suburb definitely conditioned me to be self-conscious about my appearance. And after years of developing a greater sense of confidence in the United States, I was shocked at how uncomfortable and out of place I felt in my birth country. Throngs of slender women with pearlescent complexions would glide by and I would start to critique my body and the way I talked, walked, and dressed. I reminded myself, though, that I look different because, well – because I am different! I have Korean features that I inherited from my birth parents and I have facial expressions and mannerisms that emulate my American parents. Rather than viewing myself as someone who aimlessly drifts between two worlds, I started to see myself as a unique and evolving combination of both.

MY REFLECTIONS

When I learned the news of my birth mother’s passing, I felt as if I hit a dead end. All of my pleas for answers were in vain, I told myself. Eventually, though, I began to look at things in a different light and could see beyond the impasse. Sure, I will probably never know my birth mother’s name or understand the full story behind her adoption plan. But those hiccups did not hold me back from traveling to Korea where I learned some valuable lessons along the way.

The most important thing I learned was the value of self-acceptance. Once I began to recognize and embrace certain parts of myself that I had kept on the shelf – my Korean heritage, my adoption story, all of the things that set me apart from my peers – I was able to fully appreciate myself as a whole. I no longer felt the need to fill in any blanks or cover up any holes. I might never have all the answers, but that’s life. Like every other person on this earth, I am a mosaic – made up of different parts that give me character.

My mother also reminds me often that we cannot control the things that are beyond our control. While this overused maxim inspires a lot of eye rolling from me, I know that it holds a lot of truth. When I landed in Korea, I knew that I had control over my outlook. I could maintain a tight grip on my boundaries to eschew vulnerability. Or, I could let my guard down and embrace all of the parts that make me who I am. I am grateful to have chosen the latter during my trip. By embracing all of the pieces that make me Jenna, I was able to see beyond my losses and realize the invaluable things that I had gained along the way.

MY GIFT

Near the end of my trip, my chaperone Ms. Kang casually asked me during dinner if I wanted to visit my birth city. This question made me feel tense and anxious. My natural reaction was to formulate a list of reasons as to why it was a bad idea to go. It could dredge up difficult feelings. Was it worth driving through a big city without any specific destinations? In my adoption papers, the typewriter ink bleakly reads “A Hospital in Pusan” next to the space where it asks for my birthplace. There are a dozen hospitals in Pusan and who knows if the hospital I was born in still exists. Perhaps, I can come back with John or my adoptive parents when I feel more settled. I laid my chopsticks on the table and turned my focus back to Ms. Kang who was waiting for a response. Before I could change my mind, I agreed to go. What if I had let my fears influence all of my life decisions? I would have never applied for my job at the adoption agency. I would not have searched for my birth mother or returned to Korea as an adult. I refused to let my fears stop me from visiting a critical part of my past.

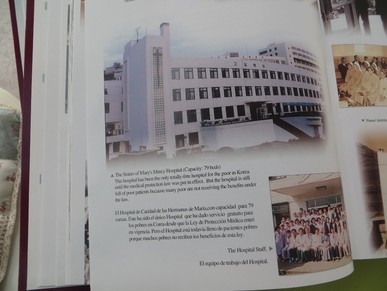

The next day, Ms. Kang drove me up and down the streets of Pusan. “Take pictures of your birth city, Jenna,” she instructed. Your birth city, I thought. I dutifully obeyed by snapping photos of buildings and random passersby on the streets. A vibrant fruit truck parked in front of a pharmacy. A congested stream of traffic inching along a steep road. Tall office buildings with signs emblazoned across their fronts, advertising age-defying cosmetics and Samsung gadgets. My hour-long photography session was interrupted by a shocking update from Ms. Kang. She explained to me that she had reviewed my adoption records earlier that day and found the hospital where I was born. “Do you want to see it?” she asked over the hum of traffic. I could not believe what I was hearing. Just when I had started to let go of my lost puzzle pieces, I was offered the chance to revisit a landmark from my past. With tears streaming down my face, I responded: Yes, of course.

As I peered down the hallway, I wondered which room I had occupied as an infant. It was the most surreal feeling to walk through a place that I had been 26 years ago. I felt like I was in a movie scene that I wanted to preserve in time forever. I remember wishing that I could just shout directives at someone through a TV screen: “Hey, you! Yeah, you, over there, sitting on the couch. Could you rewind this scene for a few seconds and then press pause?” I needed more time to absorb everything around me. Alas, I was not able to travel back in time or press pause. I obediently followed the nun and Ms. Kang down the flight of stairs to tour other parts of the hospital. But the memory of that moment remains so vivid in my mind that I am able to replay it often.

ME

When I returned to the United States last year, I was determined to write about my experience in Korea. Sitting down to write out my thoughts, however, proved to be a far greater challenge than I had anticipated. I could not believe that after all of my intense soul-searching, the hardest part would be in the quiet moments after my trip when I tried to make sense of everything. So I slammed my computer shut and walked away from writing for a while. I became immersed in my job at the agency, focusing my attention on deadlines and projects. I distracted myself with graduate school papers and reading assignments. I also started planning my wedding with John after we officially became engaged in May.

My yearlong retreat from writing came to an end a few weeks ago. My coworkers during lunch reminded me of the post I had secretly been avoiding. Oh, THAT thing? I thought, staring down at my half-wilted Caesar salad. I must have completely forgotten about it! Deep down, I knew it was time to revisit my story. I was done with graduate school and felt ready to take on the world as a new social worker. Later that night, I booted up my computer and began to feverishly type. I reminded myself of the Japanese notion of “wabi-sabi.” I embraced the imperfections rather than gloss over them. I admitted my frustrations as an adoptee. I was more honest with myself.

My trip to Korea was not the answer to all my questions. In truth, it actually dredged up more questions. Nevertheless, I understand that my story, like everyone else’s, is comprised of unfinished pieces. I may never know my complete birth history. Or have the chance to meet my birth siblings. But I can appreciate the fact that my story is an evolving work in process.

I will return to Korea someday. Next time, I hope it is with John and my family so I can show them the art galleries and markets that are tucked away in various corners of Seoul. We can traverse the country by van and take ferries to different islands just like I did with Ms. Kang. And years down the road, I will take John and our future children to the hospital where I was born so I can tell them my story. The story of how I came to know my past.